Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Unspoken Tragedy of Natalie Wood

by Anne Helen Petersen

Natalie Wood was a transitional star, her career straddling Hollywood’s awkward shift from the classic studio system to the independent free-for-all that continues to characterize film production today. Her face also seems frozen in transition from girl to woman: Wood was a child star, Oscar nominee, teen bride, and has-been — all before the age of twenty. And her acting oscillated between the poignant and the hysterical, for which she was alternately lauded and lampooned. But she had a work ethic, and ultimately survived studio manipulation to become a legend in her own right, starring in one of the most successful and seminal musicals of the past fifty years.

Before her gradual retreat from Hollywood, she appeared in a smattering of later-career films and mini-series, and was filming with Christopher Walken in 1981 when she fell from her private yacht and drowned. Her death, although deemed an accident at the time, has been shrouded in scandal ever since. The case was reopened late last year (and, as of today, re-closed), reviving our macabre interest in stars we didn’t even know we still cared about.

You can read the ins and outs of Wood’s death elsewhere. Because what’s more interesting than how she died is how she lived: as a stand-in for teens beset by angst the world over, with an image mobilized to both assuage and accelerate societal anxieties about female sexual desire.

Wood, née Natalia Nikolaevna Zacharenko, was the child of Russian immigrants, and spent her early years in Southern California. Natalia was cute, and others, including those in the film business, thought so as well, prompting her mother to move the entire family to Hollywood to pursue their five-year-old’s film career. She starred in a few movies, let RKO Anglicize her name to “Natalie Wood,” and appeared increasingly precocious — think Dakota Fanning with brown hair. Orson Welles said the adolescent Wood was “so good she was terrifying.” Her parents signed Wood to 20th Century Fox, and she soon starred in Miracle on 34th Street, effectively marking the end of her private life at the ripe old age of seven.

After a host of loving-daughter and similarly moppet-like roles, Wood co-starred in A Rebel Without a Cause. This film is bandied about by cultural theorists and ascribed with all sorts of significance: James Dean Cries a Lot — the first representation of post-war teen malaise! Dad Wears an Apron — Freudian psychology seeps into pop culture! All these things are true, but the film has accumulated a cultural heft that the actual text itself cannot support. Yes, teens rebel; yes, James Dean is a fox. But like so many teen films, then and today, the film is overwrought and overdone. I realize this is blasphemy, but my own sins against the film history canon matter less than the fact that the movie not only made stars of James Dean and Sal Mineo, it turned Wood from a child star into a bona fide teen idol — the same way that, say, the album Justified turned Justin Timberlake from an N’SYNC-er who wore head-to-toe denim into someone women actually wanted to undress.

Wood and Dean with Rebel director Nicholas Ray.

In later years, biographers and scandal mongerers claimed Natalie Wood was all over every male on the set, initiating an affair with the film’s director, 43-year-old Nicholas Ray. A highly unvetted source claims that Wood was not only sleeping with Ray but with her other costar, too — one Dennis Hopper, creating all sorts of dramz with the near-men and dad-aged-men on set.

Whether or not this was true — part of me just thinks that it fit well with the image of Wood that emerged post-Splendor in the Grass — it certainly was not public knowledge in 1955. Indeed, in Rebel Without a Cause, Wood really just seems sixteen, anxious, and totally crushing on Dean the way a sixteen-year-old should. And Wood was nominated for an Academy Award not for playing something she wasn’t, but something she was — the same way that so many children and teens are nominated (and win) for playing characters who are actually children, as opposed to children’s bodies mouthing adult words (remember the little sister character in 500 Days of Summer? That sage-advice-giving girl WAS THE WORST).

However precocious Wood may have been as a child actor, she was now playing teens — and teens, male and female, loved her. Over the course of the ’50s, the studios, already in the early stages of free-fall following a constellation of regulatory and cultural changes, began to increasingly rely on teen audiences. I know this sounds like a no-brainer, as 90% of contemporary media products cater to teen audiences, but in the ’50, this switch was A HUGE DEAL. The teenager, a cultural formation in and of itself, had not really been a thing until the Depression/World War II. Seventeen Magazine didn’t even hit newsstands until 1944. People think of the ’50s as the baby boom, but it was also the teen boom — a time when teenagers benefited from their parents’ new prosperity, using allowances and pocket money to “vote teen” at the box office. The drive-in theater was a response to geographical demands, but it was also the perfect teen magnet: there’s a reason they were nicknamed “passion pits.”

Long tangent short: to attract teen audiences, the studios — and fan magazines, and the rest of the gossip industry — needed teen idols. Dean had already established himself with East of Eden, but Natalie Wood was a studio’s dream: young, popular, and, unlike Brando and other up-and-comers, already under studio contract. In other words, she would do what her studio, now Warner Bros., told her.

And from 1955 to 1960, her studio told her to do two things:

1. Star in really shitty movies

and

2. Marry her childhood idol, all Katie-Holmes-Tom-Cruise style.

First, the films: apart from a small but crucial role in The Searchers, Wood appeared in nine stinkers, including All the Fine Young Cannibals, a bomb so big it appeared to be the end of Wood’s career.

No matter of prom shoes could save Wood’s career.

Despite critical and box office failure, Wood was all over the gossip press, in part because Warner Bros. learned that Wood had long harbored a crush on Robert Wagner, a B-level but very handsome star contracted to Fox. The studios arranged a high profile date between the two, timed to correspond perfectly with Wood’s eighteenth birthday.

I have no idea. Are they telephoning while ironing?

The two “courted” for a year and married in December 1957, inviting the gossip press along the way. At this point, more and more stars were going independent, which meant that they were no longer forced to cooperate with the fan magazines, posing for studio-approved photos and allowing studio press agents to pen articles under their bylines. The fan magazines, which once benefited from a flow of free (albeit highly fabricated) information from the studios, now had to scramble for content. Some of them did so by speculating or performing “write-arounds” — using “unnamed sources” to hide the fact that the star had not, in fact, spoken to the author. We see this all the time now, but for the gossip press of the 1950s, it was a real crisis.

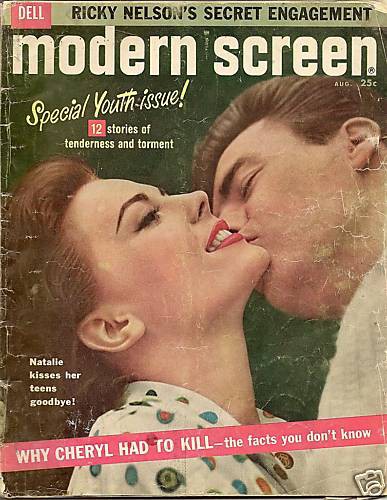

But there were still some stars who would cooperate, and the majority of those stars were still teens. Some were music and television stars — Elvis and Ricky Nelson were both big favorites — but Natalie Wood and Robert Wagner seemed to offer salvation. While Liz Taylor and Eddie Fisher refused to grant interviews, these two shared (or, more precisely, were compelled to share) their “real-life” (read: totally fabricated) wedding album and “private love diaries.”

NOTE: I AM HAVING UNPLEASANT TOM-KAT FLASHBACKS.

All this, and nary a hit to be found! The studios were confused, and even more confused when they put Wood in a film with Wagner, and even that bombed. In this way, Wood further underlined the growing disconnect between gossip stardom and film success. Wood’s private life sold magazines; Wood’s acting career did not sell movie tickets. At this point, she could probably have exhausted her celebrity by selling photos to Modern Screen the way that former Bachelorettes sell their baby photos. Yet Elia Kazan, best known for On the Waterfront and naming names during the McCarthy hearings, had a new script, and fought to give Wood a second (er, fifteenth) chance.

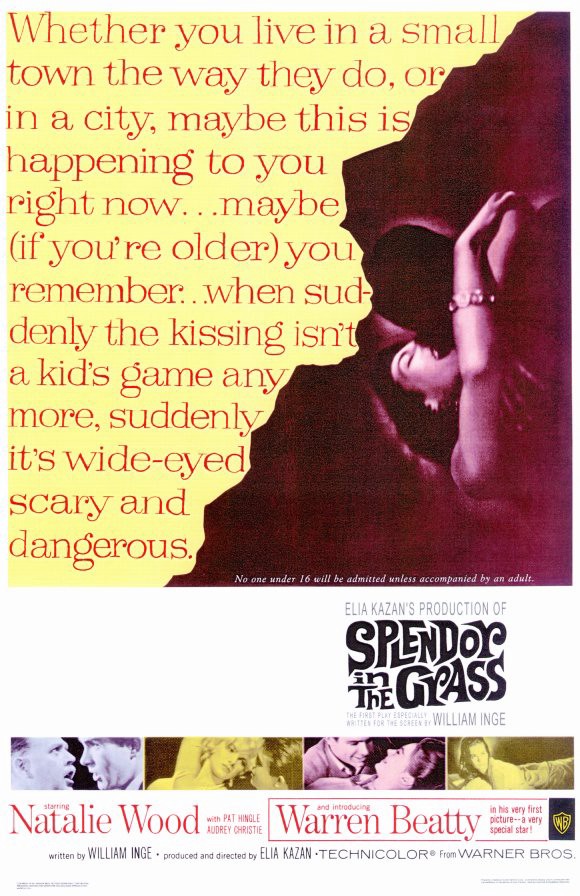

Now is the point when I try to tell you about the marvel that is Splendor in the Grass. I don’t know that I can, except to say that the sexual energy is this film is enough to power a small town in Vermont. It demands to be experienced first hand. As in so many films from the ’50s and early ’60s, this energy undulates immediately below the surface, bursting through in gasping, manic moments. It’s a story of young love set in the years leading up to The Great Depression, with a very young Warren Beatty (appearing in his first major role) devoted to a still believably high-school-aged Wood. But he REALLY, REALLY WANTS TO HAVE SEX, because, duh, he is teenage boy WITH URGES. Wood’s into it too, but everyone tells her that sex = huge slut = the end of her life = being a poor person. The horror, the horror! (Warren Beatty’s sister = a sexually “loose” flapper = slutshamed all over the place = his parent’s personal nightmare.)

Urges: Teens have them!

If Beatty can’t exercise his urges on Wood, then he’ll find someone (read: a loose woman) with whom he can. Wood finds out and is literally driven mad — like rolling-around-on-the-ground palpably crazy. Her family sells their investments to pay for their daughter to go to the sanatorium, while Warren Beatty’s family loses its collective shirt in the stock market crash. Fastforward several years, and FATTIE SPOILER ALERT: Beatty’s family is living in relative squalor. Wood’s out of the crazy house, but when goes to visit Beatty, ahhh shit he’s saddled with a wife who obviously has sad poor people sex with him all the time, because they already have one baby and another’s on the way. Plus the wife is AN IMMIGRANT! SHE’S ITALIAN! HOW DÉCLASSÉ!

Natalie realizes that their love can never be, so she returns, all Grey’s Anatomy style, to get married to her former doctor from the sanatorium. (In movies, doctors never fall in love with other doctors; they always fall in love with their vulnerable yet beautiful patients.)

The film is overwrought and, in places, overpoweringly melodramatic. But it’s also a beautifully subversive thing: we may think that sex ruins people and makes them crazy, but in reality, sexual repression ruins people and makes them crazy. And marry Italians.

I’m also in love with the marketing for this film, which relied heavily on teen identification. Every teen melodrama does this implicitly, but Splendor in the Grass’s trailers and posters made it explicit:

“If you’re an adult, you lived this story. If you’re young, it’s happening now.”

And look at this poster! You guys, if they still made posters like this, maybe we’d actually go see films in the theater on a regular basis:

Just weeks after Splendor hit theaters, Wood appeared in another film, a film even more visible than an Elia Kazan picture about sex. This picture had singing, a hackneyed Shakespearian plot, a successful Broadway run … it had SHARKS and JETS and slicked hair and tight pants and twirling skirts and DANCING IN THE MOTHERFUCKING STREETS OF NEW YORK!

I’m talking, of course, about West Side Story, in which Wood plays the very innocent and very desirable Maria Nunez, sister of Head Shark Bernando, and object of former-Jet Tony’s affection. I realize West Side Story may hold a special place in many of your musical-theater-loving-hearts, but let’s be honest: this film is ridiculous. I kinda love it — even if it is about 30 minutes too long — but it is ridiculously bad. But like all bad musicals, while the film, as a whole, may not stand up to repeat viewings, you always have the magic of the remote control edit, a.k.a. the Center Stage edit, a.k.a. fastforwarding through the talky-talk parts and just watching the dancing. This is obviously the way this film is meant to be viewed, preferably with bad Chianti for every time someone a) makes a really, really earnest face; b) gets really, really pissed off about someone from a rival gang making googly eyes at someone related to someone in your gang; or c) uses a street fixture of some sort as a dance prop.

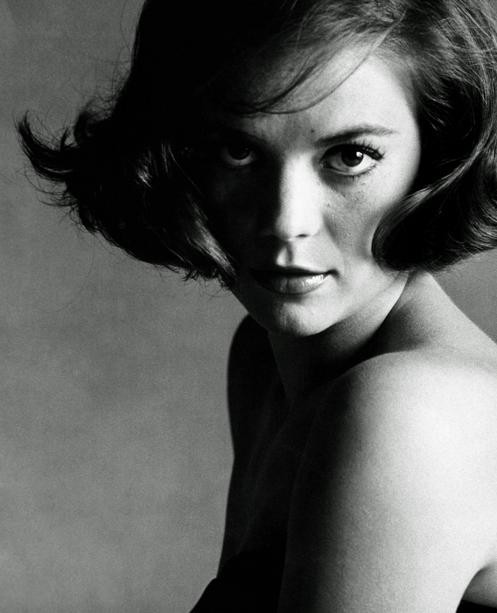

But there’s something gloriously exuberant about Wood’s performance — unlike Splendor in the Grass, where she’s purposefully repressed, here she gets to let her eyes go wide and lip-sync with as close to wild abandon as someone lip-synching possibly can. Maybe she annoyed you in Rebel Without a Cause, maybe her romance with Wagner made you ralph. But here, she gets beautiful clothes and mooney love scenes, and the result, however preposterous and campy, makes it nearly impossible to dislike her. Which is all just another way of saying that Natalie Wood, Major Movie Star, was back.

Wood’s performance in Splendor in the Grass earned her a Best Actress Oscar nomination, and West Side Story became one of the biggest grossers of 1961. Her separation and subsequent divorce from Bob Wagner only made for greater gossip fodder: stars become stars through performances; they stay stars through gossip. And the notion that Wood could be moving on with Warren Beatty, by then a rising star himself …

… the fan mags obviously went crazy, especially when Beatty accompanied a ravishing Wood to the Oscars in 1962. I mean seriously. Wow.

Wood’s next film, Gypsy, was an obvious attempt to exploit her musical success in West Side Story, only this time she played a vaudeville performer turned burlesque dancer, daughter to a shrill and toxic stage-mom (rather perfectly portrayed by Rosalind Russell).

Gypsy resides somewhere in the No Man’s Land of the absolute value scale of movies: it’s not good enough to make it good, and it’s not bad enough to make it awesome — neither Moulin Rouge nor Burlesque. It’s hanging out with most of the films made by Jessica Biel, somewhere between milquetoast and forgettable.

A string of predictably mainstream roles followed: opposite (sometime boyfriend) Steve McQueen in the weirdly moralizing Love With a Proper Stranger, inconceivable as Helen Gurley Brown in the forgettable film adaptation of Sex and the Single Girl, and oddly touching as a tomboy-turned-Hollywood star in Inside Daisy Clover (let’s be honest: the real reason to watch this film is young Robert Redford).

Hellllllllo, Robert.

In 1965, she was paid loads of money to make a slapstick turn alongside Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis in The Great Race. Wood looks gorgeous, but the film was a bloated mess and a huge bomb at the box office.

She played a bored housewife who dresses up to rob her wealthy husband’s bank in Penelope and, in 1967, paired with Redford yet again, this time in an adaptation of Tennessee Williams’ one-act play This Property Is Condemned. Wood plays a (big surprise) sexually suggestive and alluring woman attracted to a stranger (Redford), and she uses her sexuality to 1) piss a bunch of people off; 2) get her way; 3) achieve fleeting, New Orleans-based happiness; and 4) (another big surprise) DIE.

This decade demonstrated that Wood could play two parts: mad-cap and self-destructively sexual — sometimes both at once. The bifurcation seemed to spread to her personal life, too, and Wood retreated from Hollywood to seek treatment for depression (and turned down Warren Beatty’s offer to star opposite him in Bonnie & Clyde — purportedly because she refused to be separated from her therapist). Wood began dating producer and generally boring guy Richard Gregson at some point in the late ’60s, marrying him in May 1969, at the ripe old age of 30.

Then, three months later, there was Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, Bob Mazurky’s take on “swinger” culture and its various pitfalls. Natalie Wood. As a swinger. With Dyan Cannon and Elliot Gould. The marketing was obviously a study in subtlety.

As Pauline Kael, inveterate movie critic for The New Yorker and the closest I get to a personal hero, explains,

I think it’s almost impossible to watch Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice without wondering how much the actors are playing themselves. Natalie Wood is still doing what she was doing as a child — still telegraphing us that she’s being cute and funny — and she’s wrong. When she tries hard, she just becomes an agitated iron butterfly.

I mean, Kael’s right. Wood, like so many stars, was best at “acting” like herself, which is to say acting her star image. When she tried to be sexual without the neuroses, or overly cute, there was just too much try. I get it. But shit, Wood’s eye makeup and boobs in this film are just fantastic.

Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice’s subject matter was titillating, but the narrative resolution rendered it tame enough to become a major mainstream hit. Americans love the thought of transgression, not the actual act, which explains why Rihanna’s “S&M” is a huge hit while actual S&M is not.

Amid all the film’s fanfare, Wood retreated once again, giving birth to a daughter, Natasha, in 1970. But her boring producer husband was cheating on her (with the secretary, no less; how very Hollywood-screenplay of him), and in August 1971, Wood took her infant daughter and left. Super sad, I know — but then she rediscovered her childhood love! GOOD OL’ BOBBY WAGNER, THERE TO SAVE THE DAY!

And just like a Cary Grant comedy of remarriage, Wood and Wagner reunited, went through a whirlwind re-courtship, and married just five months later. Wood gave birth to another daughter, Courtney, in 1974. The 1970s version of The Minivan Majority must have been thrilled: onscreen, woman dabbles in sexual liberation and “open marriage”; off-screen, she finds out that her husband is cheating with the secretary. That’s what you get for sexual permissiveness! But don’t worry, she remarries, and not to some schlump, but her childhood crush, the man who (presumably) took her virginity. Sexual conservatism reigns supreme!

Wood operated in semi-retirement for the rest of her life, aging the way Diane Lane has, which is to say she seemed to get only more luscious with time. And then, in 1981, the yacht, the drowning, and the enduring scandal.

Wood was made famous for our generation by her death, which, yes, is sensational and belongs on Unsolved Mysteries on NBC on Wednesdays at 9 p.m. circa 1991. But in reality, it’s the least interesting thing about her — in fact, it has very little to do with Wood herself and everything to do with the type of man who would or wouldn’t save a woman who was or was not calling for help, and how each of these men has worked to exculpate himself in the years since.

Ultimately, I’m less interested in thinking about these men and more interested in re-watching Wood’s movies, recreating her eye makeup, and staring at the dozens of exquisite shots that pop up when you type “Natalie Wood Warren Beatty” in Google Image search. People think the scandal was Natalie Wood’s death. But the real scandal was the way in which women — specifically, the dozens Wood portrayed, along with Wood herself — bore the burden of our culture’s conflicting, schizophrenic, fucked up attitudes toward sex.

Wood didn’t have tragedy mapped on her body the way that Marilyn Monroe or Judy Garland did. The signs of her struggle were far less obvious, in part because her rise was less mercurial, her handling of stardom somehow more balanced. She was a survivor, as cliched and Hallmark-movie-of-the-week as that sounds, and at various points in her career wielded more power than any of her male co-stars. She wasn’t a tremendous talent. She couldn’t really sing or dance. But she was a sex symbol for twenty years in a time when “sexual” was simultaneously the best and the worst thing a girl could possibly be, and she lived to tell the sad, screwy tale. And that, more than playing opposite James Dean, more than working herself into a true frenzy of repressed sexuality in Splendor in the Grass, evidences true talent. Not as an actress, per se, but as the makings of an image that will continue to endure.

Previously: Cary Grant’s Intimate Bromance.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.