Scandals of Classic Hollywood: The Unheralded Marilyn Monroe

by Anne Helen Petersen

What’s left to say about Marilyn Monroe? I mean seriously, what can I tell you? She was beautiful, she had a body, she dripped sex, plus all of the other clichés in the sexy-lady-describer book. I had all of this explained to me at some point in my teens, but it didn’t really sink in until the first time I saw her on the screen — at some point in my early 20s, in Some Like It Hot — and I finally understood what all the fuss was about.

After you see her onscreen, you think you understand, but even then, you don’t. Because today’s Monroe, the Monroe that has been flattened into posters, Warhol-ed, turned into pulp biographies, and evacuated of all actual meaning, is a mere shade of the Monroe that bulldozed through the ’50s. Today’s Monroe is a time capsule: The public used to like curves in actresses! Visceral sexuality, stars had it!

But in the 1950s, Monroe was a presence impossible to ignore. Her image signified vitality and brazenness, sexuality and innocence. It reset the standard of what it meant to be sexy, and what it meant to be sexy in public. No star has troubled the status quo as significantly since.

But what made Monroe more than a sumptuous body and a breathy voice was, of course, her life — and more importantly, the way that she and others spoke about it. Because Monroe also had business acumen, personal volition, and a startling, if subtle, awareness of her own image. She made her studio, 20th Century Fox, a tremendous amount of money in the 1950s, when predictable hits were few and far between. Yet Monroe was no meek studio star. She tested the weakened boundaries that governed star contracts in the early ’50s, and fled Hollywood, formed her own production company, and chose her own projects.

Monroe “acted out what mattered” to people in the 1950s — which is to say, she acted out sex — and did so in a manner that seemed to heighten and soothe anxieties about sexuality during the era. Sexuality was the very foundation of Monroe’s star image, and her studio, her agent, and Monroe herself had zero qualms about forwarding that image. Ten years before, Monroe’s image never would have been possible, let alone palatable. In the 1950s, however, it reconciled innocence and sexuality — the amalgamation of the virgin and the whore — in a manner that seemed to arouse and appease sexual appetites without guilt or shame.

But let’s go back: Monroe spent most of her childhood being traded among foster homes and extended family, dropping out of school to marry the son of a next-door neighbor, getting a start in modeling, divorcing, and posing for cheesecake photos (read: soft porn, usually printed in calendar or trading card form) to make ends meet while trying to make it in Hollywood.

To scrap her way to the top of the Hollywood heap, Monroe relied heavily upon a very powerful and much older boyfriend. This boyfriend — Johnny Hyde — was an agent at William Morris, one of the most powerful agencies of the post-war era.

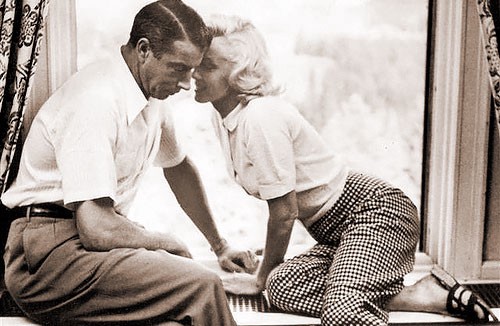

A very young Monroe and a very wooly Hyde.

Hyde was absolutely besotted with Monroe, and helped land her a string of bit-parts, including a small but significant turn in All About Eve. Have you seen this film? If not, then how will you possibly understand what it feels like when you’re in your 40s and used to be fabulous and are, still, arguably fabulous, if not even more fabulous, but everyone keeps looking at some hot piece who’s 20 and wears those Nike exercise shorts all the time even though she doesn’t even exercise and has great skin and steals all the attention and men? I mean, that’s basically the plot of All About Eve, give or take a few gin-pickled evenings with Bette Davis, and even though it sounds like a weepie, it is hilarious times 10.

Point is, Monroe plays a dim-witted actress willing to sleep with those above her to make it to the top, and the part established the ground note of Monroe’s image. Over the next five years, her roles would be variations on the same theme: beautiful, seemingly clueless girl smartly manipulates others’ reactions to her body in order to get what she wants.

Hyde was slowly dying, but he set the table for the feast that would be Monroe’s future, arranging private acting lessons, nabbing Monroe a Photoplay profile, and securing Monroe a seven-year contract with 20th Century Fox. When Hyde passed away at the end of 1950, Monroe’s future was secure. Her film roles remained, for a time, unremarkable, yet her exposure was growing. She was a regular feature on Stars and Stripes, the magazine for soldiers in Korea. Look and Life both put her on their cover, and various “Monroe-isms” — “I never suntan because I love feeling blonde all over” — were in wide circulation.

A high-profile romance with Joe DiMaggio made her a fixture in the gossip columns, and theater owners began putting her name above classic stars like Ginger Rogers and Cary Grant. Wherever the Monroe name and image appeared — on the screen, in the pages — profits followed.

But America was conflicted: Who was this lady, all bosomy and breathy and taking over all the magazine covers? Did readers feel the same sort of curious anguish and confusion that I felt when some normal-looking lady with an asymmetrical haircut and 52 babies started taking over People and Us in the summer of 2009?

One male Photoplay reader complained that Monroe “seems to think that the only way she can get noticed is to shed her clothes,” yet conceded, “I don’t mean that she should hide those gorgeous curves … but she doesn’t need to disrobe to appeal to us men. I enjoy looking at her, who wouldn’t?” Translation: “I totally want to see Monroe naked, but maybe if I send this letter to my wife’s fan magazine, I’ll convince both her and myself that I don’t?” This reader, like many other fans, was drawn to Monroe, yet conflicted about the way SHE WAS TOTALLY MESSING SHIT UP.

Photoplay addressed the conflict head-on with a November 1952 article, ostensibly penned by Monroe herself, that essentially suggested that Monroe was sexual because:

1) She was vulnerable and lonely.

2) She had a troubled past.

AND MOST IMPORTANTLY…

3) She had no female friends to tell her when to put it away.

Put differently, she was lacking a Hairpinnerverse.

Monroe — or, rather, the press agent writing as Monroe — also played to female readers’ concerns about the star’s actions, admitting:

Up until now, I’ve felt that as long as I harmed no other person and lived within the bounds of good taste, I could do pretty much as I pleased. But I find that isn’t really true. There’s a thing called society that you have to enter into, and society is run by women. Until now, I’ve never known one thing about typical ‘feminine activities.’ … All I know about cooking is how to broil a fine steak and make a good salad. That, you see, is all any man wants for dinner … I don’t sew. I don’t garden. But now … I’m beginning to realize that I’m missing something.

That missing something: female friendship, duh. Marilyn just wants to be BFFs, homely fan magazine readers! She’s totally not trying to make your husband masturbate to your picture in the bathroom while you’re making pot roast!

As hokey as the article might seem, it was doing some serious damage control. Monroe’s studio understood that Monroe’s appeal, at least in the early ’50s, was lopsided. For her to become an authentic star, as opposed to a Megan Fox-esque sex object, her seemingly intrinsic sexuality needed to be complemented with an authentic sense of humanity, supported by pleas for protection and affection. Monroe needed women to like her, and articles like this one — along with dozens of other interviews, all playing up her vulnerability and innocence — went a long way toward making that happen.

The years 1953 and 1954 marked the height of Monroe fever — a fever that was at once a symptom of America’s fascination with sexuality and a catalyst for that fascination, kinda like how my Anthropologie habit is both a symptom of my white yuppieness and a catalyst for continued white yuppieness. During this period, Monroe appeared in a a quick succession of films — Niagara, Gentleman Prefer Blondes, and How to Marry a Millionaire — that essentially made her into a huge, no-fucking-question star.

Sure, she basically plays the same part in all three. Sure, Niagara is 88 minutes of characters pretending they’re involved in a film noir, as opposed to a film based solely on what it feels like to look at Marilyn Monroe. You can see the tension here:

(Niagra also has an amazing scene where, when asked why she put on a particular song, Monroe replies “There are no other songs.” I know the feeling, Marilyn. That’s how I responded when people asked me why I listened to Katy Perry’s “Teenage Dream” for five weeks straight).

And okay, fine, How to Marry a Millionaire is derivative. BUT YOU GUYS, Gentleman Prefer Blondes is a stone cold classic.

It’s a classic for Jane Russell’s dance routine with a troupe of near-naked synchronized swimmers (please watch. Please. I guarantee it will be the queerest thing you see all day), but also because Monroe’s character, Lorelei, is a near-perfect projection of Monroe’s star image.

Monroe plays up her man-eating, money-hungry image in a publicity still.

Through her performance, Monroe hints that Lorelei’s dumb-blonde-ness is all an act — a very deliberate means to an end. Which would mean, by extension, that the Monroe star image could also be a very carefully constructed act. In this way, Monroe and her director (the brilliant Howard Hawks, champion of strong female characters) make the strings of her studio puppetry visible, but only to those who were willing to see.

Off-screen, Monroe’s popularity continued to snowball: Photoplay named her Star of the Year and, in January 1954, she married Joe DiMaggio. What’s more, 1954 was, as all of you with past lives in women’s and gender studies know, the year of the Kinsey Report on Women, which created a huge, anxious, oh-no-girls-masturbate shitstorm of media coverage. Monroe ostensibly had nothing to do with the Kinsey Report — or did she have everything to do with it?

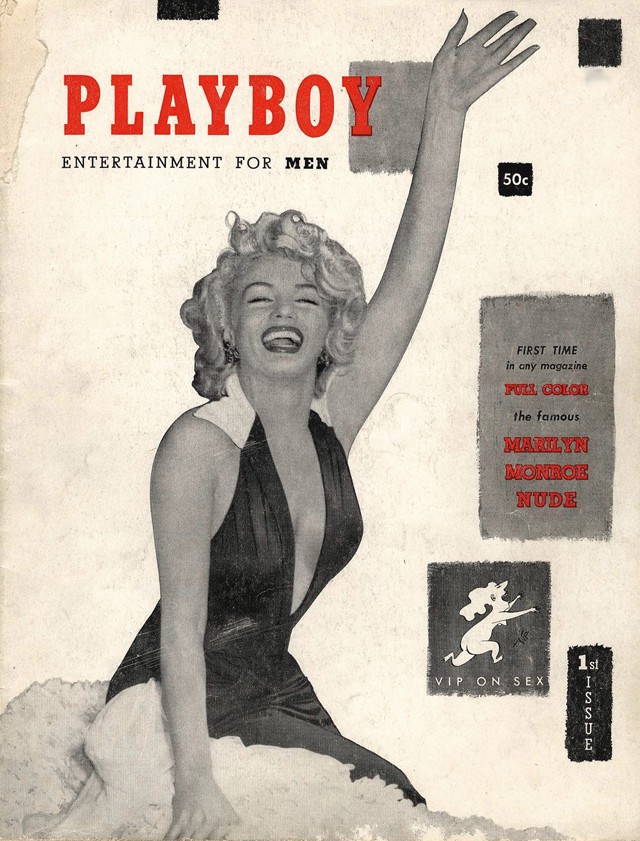

But we are not even close to done. Because 1954 also marked the inaugural issue of Playboy. And I will give you one fattie guess who was on the cover.

There was Monroe, in a photo taken during her tenure as Grand Marshall of the 1952 Miss America Parade. Please, take a moment, forget every time you have gone to Vegas and witnessed bachelorette parties full of girls scheming for drinks, and look at that dress with fresh eyes. That dress was smokin’. It had sparked a huge debate back in 1952 and was perfect for Playboy, evoking the brazen, guilt-less sexuality that a very, very young Hugh Hefner wished to associate with his fledgling brand.

Of course, the real money shot was the magazine’s very first centerfold: a reprint of Monroe, posing nude, from the “Golden Dreams” calendar. Monroe had posed for art photographer Tom Kelley all the way back in 1948, and the photos had been reprinted in numerous calendars, of which “Golden Dreams” was the most famous. (Pictures available here.)

When Monroe’s star rose in the early ’50s, she was identified as the model in the photos. But her response to the revelation became as fundamental to her image as the photos themselves. Instead of attempting to avoid or deny the rumors, Monroe answered them head-on: She had been “hungry,” was “three weeks behind with rent,” and had insisted that Kelley’s wife be present. “I’m not ashamed of it,” she averred. “I’ve done nothing wrong.”

Once the potential for scandal had dissipated, she promised “I’m saving a copy of that calendar for my grandchildren,” admitting “I’ve only autographed a few copies of it, mostly for sick people. On one I wrote ‘This may not be my best angle.’”

And this is where you must realize that Monroe was not dumb. “This might not be my best angle”??? That shit is HILARIOUS. And by confronting the rumors, Monroe had performed an incredible feat of public relations: She transformed a potentially scandalous story into one that further bolstered her image. And it was this understanding of sex — as something that one need not apologize for — that Playboy and Monroe both represented.

Later in 1954, Monroe was at the center of another scandal, this one involving the Photoplay Gold Medal Awards Dinner — the People’s Choice Awards of its day. Monroe showed up very late, long after the rest of the major stars had been seated. Please picture Mila Kunis arriving late, and instead of sneaking in through the back, just sauntering down the carpet. Or, take this description, courtesy of the gossip columnist Sheilah Graham:

Monroe “wriggled in, wearing the tightest of tight gold dresses. While everyone watched, the blonde swayed sinuously down the long room to her place on the dais. She had stopped the show cold.”

In short: Girl made an entrance.

Joan Crawford denounced Monroe’s “burlesque show,” claiming ‘Kids don’t like Marilyn … because they don’t like to see sex exploited.” Photoplay played up its role as “host” of the feud, sensationalizing the story under the title “Hollywood vs. Marilyn Monroe.” And let me tell you, this article is a doozy. After hooking the reader with the promise of sex and scandal, the author turns moralizing: Everybody knows that Crawford had been a “hey-hey” girl (a.k.a. big floozy) in the late ’20s; who was she to shame Monroe?

The article also made it clear that the fan magazines were shifting alliances. Joan Crawford, a steady presence in the magazine for over two decades, was out; Monroe, in all of her glittery slinking magazine-selling-ness, was in. Monroe’s agent and the gossip industry had come to some sort of understanding: Defend Monroe in the magazine, and we’ll give you some dish. Indeed, the next month, Photoplay boasted its “SCOOP!” of intimate details of the Monroe-DiMaggio romance.

And here’s where it gets all gross and anti-feministy, with Photoplay framing her marriage to the uber-conservative DiMaggio as a catalyst for a profound personality change. At home, where their lives were “as ordinary as a couple’s in Oklahoma City,” Monroe “slips into an apron and begins opening cans and getting things ready for the big fellow’s dinner, which she cooks with her own hands.” Another article proclaims Monroe’s marriage philosophy, which called for “candlelight on bridge tables, budgets and dreaming of babies” — simple, plain, domesticity. “Joe doesn’t have to move a muscle,” Monroe boasted. “Treat a husband this way and he’ll enjoy you twice as much.”

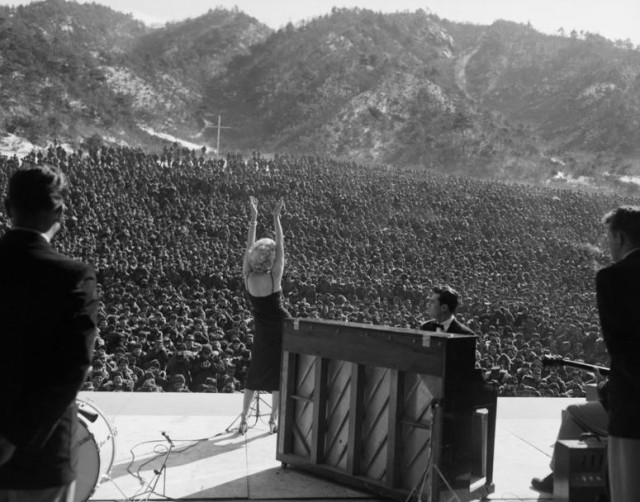

But the rhetorical masonry of the fan magazines buckled under the weight of Monroe’s preexisting image. Even as Monroe proclaimed subservience to DiMaggio during their honeymoon to Japan, she detoured to Korea to appear in 10 shows for 100,000 eager servicemen. As she and DiMaggio played house for the press, Monroe privately complained that “Joe’s idea of a good time is to stay home night after night looking at the television.”

Entertaining tens of thousands of sex-starved troops in Korea: Not Joe’s idea of a good time.

A few months later, Billy Wilder invited the press to observe the filming of the now-famous “air vent” scene for The Seven Year Itch. Hundreds surrounded the shoot as Monroe’s dress flew high, infuriating DiMaggio and inciting a yelling match between the two. They’d divorce soon thereafter, confirming the unspoken speculation that Monroe’s sexuality and DiMaggio’s domesticity could not coexist.

Monroe extended her newfound independence to her career, leaving Hollywood and 20th Century Fox in early 1955. It wasn’t the first time that Monroe had rebelled against her studio — in late 1953, she balked when Fox cast her in yet another derivative song-and-dance film, The Girl With the Pink Tights. Eager to appear in more serious roles, Monroe refused to report to the set. Fox put her on “suspension,” which meant that she couldn’t work, and whatever time she was “out” would be added on to the end of her contract. But Monroe was far too valuable to keep out for long, and Fox soon negotiated a deal: Monroe would appear in the mediocre There’s No Business Like Show Business in exchange for the coveted lead in The Seven Year Itch. But after Itch wrapped production, Fox persisted in type-casting her. Monroe was fed up, and acting on the advice of photographer and confidant Milton Greene, she retreated to New York. “The New Marilyn” was born.

“The New Marilyn” attempted to shed her one-note image and cultivate her acting skill, sitting in on classes at the Actor’s Studio. With Greene’s assistance, she self-incorporated, forming Marilyn Monroe Productions. And when The Seven Year Itch proved an ENORMOUS hit, Monroe had the upper hand against her former studio. She renegotiated her contract, leveraging profit participation for her production company and the authority to reject any script or director.

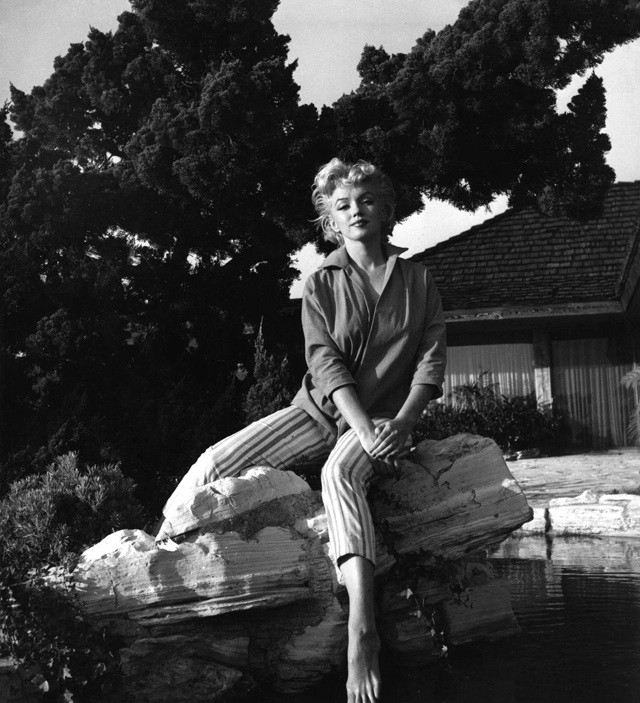

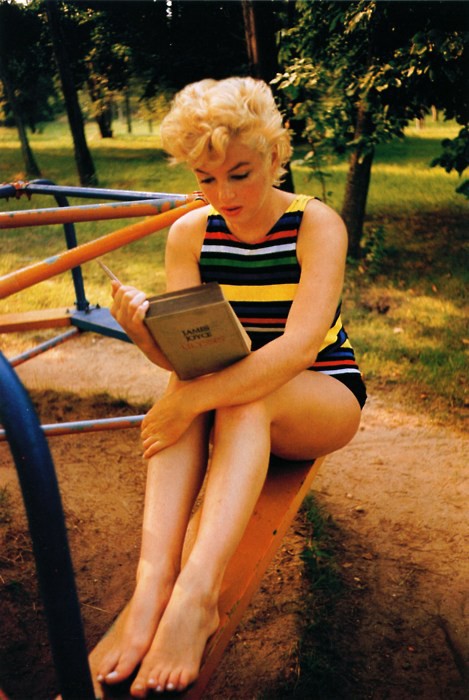

Monroe looking not at all out of place at the Actor’s Studio.

Most doubted the sincerity of her ambitions, but her performance in Bus Stop, the first film under her new contract, received the best notices of her career. (Have you SEEN this film? For me, it’s the saddest of all the Monroe films, if only because it showed how extensive Monroe’s range could be, and how little that range had been tested.)

During this period, Monroe began her relationship with playwright Arthur Miller, best known for those little plays Death of a Salesman and The Crucible. He was 11 years older than Monroe and only slightly less goofy looking than DiMaggio, but the two soon married. Never before had a major star attempted to renovate her image so radically on her own accord.

The gossip industry struggled to reconcile this “New Marilyn” with the Monroe of old. The incongruities were immediately apparent. To announce her production company and new direction, she called a press conference in New York wearing a full-length white ermine coat, which obviously screamed “I’M VERY SERIOUS ABOUT MY ART.”

When asked for names of potential projects she’d like to pursue, Monroe replied “The Brothers Karamozov.” She meant, of course, that she would like to play the lead female role of Grushenka. Her response, however, was (purposely) misinterpreted, and word spread that she wished to play one of the brothers, which just made her and her erudite aspirations look absurd. A Monroe-ism also began to circulate concerning her production company: “I feel so good,” Monroe purportedly told a wardrobe assistant, “I’m incorporated, you know.” The press persisted in reading Monroe’s old image into her new one, effectively suggesting the “New Marilyn” as little more than publicity stunt.

The gossip industry’s other tactic was to explain Monroe in terms of battling images. The Saturday Evening Post divided Monroe into three parts: “the sexpot Monroe” of the early 1950s; “the frightened Marilyn Monroe,” from the tales of her childhood; and “the New Marilyn Monroe,” a “composed and studied performer.” Photoplay distinguished between Monroe “The Legend” and Monroe “The Woman.” “The Legend” was draped in furs and jewels, responsible for “Monroe-isms,” and “robbed The Woman of friends, love, and peace of mind,” while The Woman was “shy, hesitant, removed, and terribly lonely.” Monroe’s marriage to Arthur Miller offered “The Woman” a third chance at happiness, but only if she could put the “frankenstein-like Legend” to rest. And “The Woman also becomes a mother.”

Now we will pause while I go cuddle under my feminist blanket for a little while and recover.

The bifurcation of Monroe’s image served a distinct ideological purpose: sexuality and intelligence, sexuality and happiness — those can’t co-exist! Only dumb girls are sexual; sexual girls all end up miserable. In order to make Monroe (and liking Monroe) less transgressive, the magazines had to siphon off and condemn the sexual components of her image, at least within their pages.

In hindsight, this is all pretty hilarious, and it might have read that way at the time as well. But it’s also evidence of the intense work that media outlets had to do to explain and neutralize a figure like Monroe, overdetermined, as she was, by the sexual anxiety and pleasure of an entire nation.

We all know how Marilyn Monroe’s story ends. She collapsed under the weight of her image — her thing-ness, a feeling she despised. This ending is tragic, but it’s important to recall that Monroe challenged the status quo for appropriate female behavior, and made sex visible after a long history of sublimation on the screen. She also confronted, even flaunted, the rules that had theretofore governed acceptable behavior for a star contracted by a studio. At the same time, she proved an immensely lucrative asset to a struggling studio, and leveraged the resultant power against the studio to her artistic and financial advantage. In other words, she was one savvy lady, and much, much more than the sum of her beautiful parts.

Previously: Ava Gardner, the Second-Look Girl.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.