Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Lana Turner, Sweater Girl Gone Bad

by Anne Helen Petersen

Lana Turner never looks the same. I’ve seen her in hundreds of pictures and dozens of films, and each time she looks like a slightly different person. Turner was a chameleon, a Hollywood-made confection, a liar, a victim, and a real-life femme fatale, party to one of the most infamous — and tragic — Hollywood scandals. Her image combined sex appeal and vulnerability, both imbued with a sense of danger. At the height of her career, Turner seemed a beautiful yet wounded animal, ready to lash out.

Turner’s story was sordid from the start. She was born in Wallace, Idaho, which might not mean anything to you, but as one of the 5223 users of the internet who grew up in Idaho, I can tell you that it can mean ONLY BAD THINGS. Now Wallace = meth heads, bad teeth, and lots of venison stew; in the 1920s it meant all of those things, only exchange “bathtub liquor” for “old RV meth” (sorry Northern Idaho friends, but the truthiness hurts).

Her father was a miner and a ne’er do well, and when Turner was six — that is to say, when she was just old enough to get a real good dose of Idaho in her — the entire family moved to San Francisco. Her father was killed at the end of a card game gone wrong, and Turner’s mother hauled her to Los Angeles, where Turner was shuffled from the house of one friend to another. As Turner later put it, “I was a scullery maid, a cheap Cinderella with no hope of a pumpkin.”

Until, that is, she was discovered by Hollywood at the age of 16. As her publicity team sold it, an agent spotted her sitting at Schwab’s Pharmacy in Los Angeles wearing a tight sweater, daintily licking an ice cream cone, and asked her if she’d like to be in pictures, to which she replied “I’ll have to ask my mother.” The story was a fiction — in actuality, Hollywood Reporter editor Willie Wilkerson spotted her at the downmarket Top Hat Cafe, where she was skipping school and probably eating a chicken fried steak.

But the story, however bullshit infused, helped reinforce the notion that stardom was accessible to anyone — even anonymous girls in sweaters at the ice cream shop.

And in the beginning, Turner’s image was all about this sweater. In her first major film, They Won’t Forget, she played an oversexed schoolgirl, which Turner later described as “A Thing” who “wore a tight sweater and her breasts bounced as she walked . . . a tight skirt and her buttocks bounced . . . She moved sinuously, undulating fore and aft . . . She was the motive for the entire picture . . . the girl who got raped.”

WHOA. Um, do you think I could get Lana Turner to read that to me? Wouldn’t that be hot? Especially if she stopped before the last part?

Turner’s undulation incited strong audience reaction, and pin-ups of Turner began to circulate. She was crowned “The Sweater Girl,” which, at least for me, brings to mind images of Norwegians in thick, musty nordic sweaters, but this was a different type of sweater. It was short sleeved, tight on the breasts, and kinda looked like it had been shrunk in the wash — the sexy sweater.

Its sexiness stems not from the garment itself, but from suggestion — a body bursting to get out yet still contained and, as such, safe. The sexy sweater became a primary means of conveying sex, modeled by Turner, Jane Russell, and other busty stars of the era. As the visible thong was to the early 2000s, so the tight sweater was to the early ‘40s.

The role helped earn Turner a contract at MGM, where she would stay for the next 20 years. In 1938, a contract with MGM meant musicals, playing Clark Gable’s love interest, and the services of the studio’s Fixers. She dyed her hair blonde (we’re talking Gwen Stefani blonde, not Cameron Diaz blonde) and through a series of roles in films aimed at teens, she became popular with the college boys, which is another way of saying she took the Megan Fox route to stardom. The studio sold her as All-American and wholesome, and her roles, youth, and blondness all seemed to match.

But in 1940 she began compromising that image. Instead of a nice courtship with, say, Andy Hardy or Mickey Rooney, Turner went on a date with Artie Shaw, the most popular big band leader of the era and a man 11 years her senior, and up and got married. Like THAT NIGHT, at the point when most of us are trying to decide if letting a guy buy another Gin & Tonic is going to require a make-out sesh as quid pro quo.

Most people you like after a few cocktails turn out to be weird, assholes, drunks, or boring, and Shaw was pretty much just an asshole. They fought, Turner got supposedly pregnant, he denied the baby was his, she had an abortion, and they divorced — all within four months.

MGM’s publicity department rolled with the punches, inflecting Turner’s All-American image with touches of “passion” and impulse. The studio moved her from JV to Varsity, casting her in four films with Clark Gable, who, as all good Hairpinners know, skeezed on all MGM stars, especially impulsive ones with nice sweater boobs.

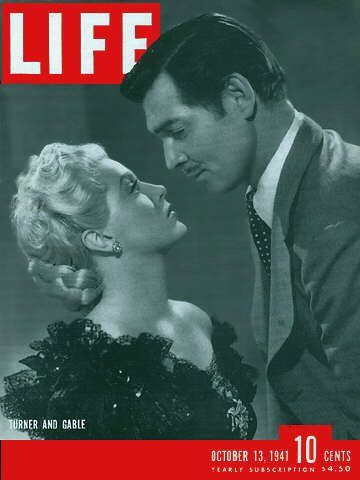

There’s no proof that anything happened between them, but it was a publicity department’s dream. Lots of coded language in the fan magazines, a steamy picture on the cover of Life, a huge desire to see their chemistry onscreen, but no actual mess to clean up. That’s when gossip does its best work — when it makes you buy the products in which the stars appear, not just the magazines in which the gossip appears.

Turner married again on impulse, only turns out Asshole #2 wasn’t actually divorced from his first wife. The marriage was annulled, the non-husband attempted suicide, Turner found out she was pregnant, and they remarried “for the sake of the baby.” This baby, Cheryl Crane, will become VERY IMPORTANT to the story in about 500 words. At the time, however, the baby added a bit of maternal ordinariness to Turner’s image, until, naturally, she divorced the guy. As my academic super-crush Richard Dyer explains, the structuring tension of Turner’s image was beginning to coalesce: “what she touches turns bad, but is that because she is bad or because she is irresistibly attracted to the bad?”

This tension was further elaborated in 1946, when Turner convinced the studio to cast her as the femme fatale in The Postman Always Rings Twice. The film was what we now call a film noir, but at the time was just a movie based on a hard-boiled crime novel, with a plot that hinges on the effect of a beautiful, damaged, and desperate woman on a susceptible man.

Watch this clip; it will tell you all you need to know. No seriously, watch it right now, even on mute — I promise lipstick and thighs and hamburgers.

I mean, THIS IS IT, right? Like there’s no need for another seduction scene ever? And the high-waisted white shorts and the knotted crop top … does Urban Outfitters carry those in my size? Can someone teach me how to make my towel topknot look like that? Do I need to live in the South, seduce some guy who comes to the diner owned by my old boring husband, and get him to kill said husband?

The film was a smash, and the first to prove that Turner could actually act (kinda like when Tom Cruise was in Born on the Fourth of July, a memory now shrouded by too much couchjumping, thumbs-upping, and Joey/Katie Holmes-lobotomizing) and reinforced her image as a woman with the potential for malice.

Over the next decade, Turner married and divorced, married and divorced, first to a millionaire, second to actor Lex “Tarzan” Barker. She dated dozens of men in between, and the rumor was that she, like that goody-two-shoes Grace Kelly, truly loved sex. As one MGM executive explained, “Lana had the morals and attitudes of a man … If she saw a muscular stage hand with tight pants and she liked him, she’d invite him into her dressing room.”

[UM, IS IT JUST ME, OR ARE YOU LIKING THIS GIRL MORE AND MORE?]

In order to explain Turner’s rapidly accumulating ex-husbands, MGM did something genius. They admitted that Turner’s “origin” story — that her father was a stand-up guy, that she grew up in a happy home — had been fabricated for publicity, and that she was, in fact, the damaged product of a broken home. In a time when pop-Freudian concepts of psychology were increasingly popular, it was easy to explain Turner’s mistakes, both at love and in life, through her relationship with her abusive father, who was equally inclined towards “badness.” (Publicity departments and fan magazines manufactured similar explanation stories for dozens of misbehaving stars, most notably Marilyn Monroe. The overarching idea: You like sex because you were poor.)

By 1956, the trouble Turner caused at MGM had begun to outweigh her value, and the studio opted not to renew her contract. Which isn’t to say that Turner was out of work: she made Peyton Place, a film so melodramatic and soapy it’s like Gossip Girl times Desperate Housewives to the everything-Nicholas Sparks-has-ever-done power.

And, most importantly, she started dating a mobster.

Johnny Stompanato was a decorated ex-Marine, a well-known clothes horse, the former bodyguard of Mob kingpin Mickey Cohen, and “the Adonis of the Underworld.” (Thanks for that one, Los Angeles Times.) He and Turner began associating at some point in 1957, and, while the details are hazy, it’s clear that Stompanto followed Turner to Europe where she was filming Another Time, Another Place. She and Stompanato then absconded to a private villa in Acapulco (how very Jen Aniston of you, Lana) and, after two months, made a very public return to the United States, greeting Turner’s daughter while looking very tan and very Sopranos.

Of course, Turner denied that she and Stompanato were involved. “There is definitely no romantic interest between us,” she declared, as they had obviously spent the last two months playing Gin Rummy and talking about feelings. Back stateside, the “non-relationship” quickly turned sour. Turner and Mr. Stomps-a-lot were constantly fighting, apparently because she refused to take him to the upcoming Academy Awards. (Can you imagine? That’d be like Jennifer Aniston taking The Situation to The Golden Globes. I. WOULD. DIE. and go to gossip heaven.)

Turner tried to jettison Stompanato, he refused, and on April 4th, the fighting escalated in Turner’s bedroom. According to later testimony, Stompanato threaten to cut, disfigure, and maim Turner. The 14-year-old Crane, fearing for her mother’s safety, grabbed a 10-inch kitchen knife and stabbed Stompanato in the stomach. He collapsed, Crane fled to her room, and Turner called her mother, who called the police. Stompanato was pronounced dead on arrival.

A shit-storm obviously ensued. There was a giant mobster dead on Turner’s pink carpet, Crane was sent to juvie, the mob was pissed, and Turner had no studio publicity team to help clean up the mess.

The weeks to come featured a series of accusations and denials: one day, Turner claims she had never encouraged Stompanado’s affections and he was essentially obsessed with her; the next, the police reveal that a photo of Turner was found on Stompanado’s person, inscribed in Turner’s hand with

Para Juanita, mi amor y mi vida — Lanita.

OH NO SHE DIDN’T!!!

But it totally gets better: Not only did Turner paint “Juanita” as a stage-five clinger, but the chief of police told the papers that Stompanado was “a gigolo type,” and, further, that “this gigolo type of behavior is not unusual. They’re always beating their women.”

OH FUCK NO HE DIDN’T!!!

Mickey Cohen was pissed. He came forth with dozens of love letters, taken from Stompanado’s house, in which Turner addressed her “Juanita” as “My Dearest Darling Love,” “Honey Pot,” and “Daddy Darling.”

All of this back-and-forth made front page news across the country, culminating in a coroner’s inquest to determine whether the killing was justifiable homicide. Turner’s testimony was a tour de force and, naturally, recounted at length:

As she answered the questions….she stared down at her twisting hands or out over the heads of the spectators — as though mumbling the details of an incredible nightmare ….The actress closed her eyes, touched at her face and continued. ‘He grabbed me by the arms and started shaking me and cursing me very badly, and saying that, as he had told me before, no matter what I did, how I tried to get away, he would never leave me, that if he said jump, I would jump; if he said hop, I would hop, and I would have to do anything and everything he told me or he’d cut my face or cripple me….’

…..Miss Turner closed her eyes again for a moment blinking and tears forming there. ‘And if…when it went beyond that, he would kill me and my daughter and my mother. He said no matter what, he would get me where it would hurt the most — and that would be my daughter and mother.

Seriously, HIGH DRAMZ!

It was, as many a journalist put it, the performance of Turner’s life. Coincidentally, Peyton Place, in which Turner’s character also takes a dramatic turn on the witness stand, was still very much in theaters. Turner’s textual and extra-textual lives were converging, and suddenly the film, up to then a modest success, become a phenomenon.

All charges against Crane were dismissed, but the months to come were filled with speculation. Was Turner involved with the Mob? Was the star of The Postman Always Rings Twice blaming a murder on a daughter? AND OHHHHHHH SHIT WHAT IF CHERYL KILLED JOHNNY BECAUSE SHE WAS SECRETLY IN LOVE WITH HIM?

Peyton Place earned Turner an Oscar nomination, but her next two films, neither of which exploited details from Turner’s life, were flops. Then, with no contract and few prospects, she took a huge pay cut to appear in Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life. This film is like everything that’s great about Turner and her image to the most lavish and over-the-top degree: over $1 million in costumes, a plot involving a single mother who shirks her duties to become a famous actress, an orchestral score to kick all other orchestral scores’ asses, and a teenage daughter who falls in love with the mother’s boyfriend. I WONDER WHERE THEY THOUGHT OF THAT?

Imitation of Life was a hit, even if it was, at the time, panned by critics. (Now all critics want to have Douglas Sirk’s melodramatic German babies, but bygones.) Yet it would be Turner’s last hit: She was nearing 40, and the luster, vulnerability, and threat seemed to have faded. In her final films, she seemed a shell of herself, inhabiting the Turner image but not owning it. Turner married three more times, including, most dismally, to a nightclub hypnotist who absconded with her money, and retreated from the public view.

Turner is remembered for her role in the Stompanato killing, but what amazes me is how exquisitely the event fit within the trajectory of her image and life. It’s as if all of her roles, marriages, and dalliances were leading up to that night and the peak performance on the witness stand that followed. Which is why, for all of the hoopla, Turner could remain a star: It fit seamlessly with her image and, as such, was not scandalous so much as scintillating.

Turner wasn’t pitiable like Judy Garland, wasn’t strong like Joan Crawford, wasn’t childish like Marilyn Monroe. Rather, she was dangerous in a way that few other female stars seem dangerous: She was never aggressive, per se, but she was manipulative — able, through her beauty and sexual appeal, to get others to do what she wanted, on and off the screen.

That sort of power destroys, especially when wielded indiscriminately. In this way, Turner’s contemporary analog might be Britney, another blonde sold as an embodiment of the American Dream. When Britney’s power led to choices that seemed to betray a souring in that Dream, it forced us to reconsider the package we had been sold, why it had been so attractive, and the destructive machinations necessary to make that dream a reality. In the end, both Britney and Turner inhabited and were betrayed by an imitation of life — and that’s the most tragic plot line of all.

Previously: Clark Gable, the Scandal That Wasn’t.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.