Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Ingrid Bergman, Instrument of Evil

by Anne Helen Petersen

Through some undergrad film class, ennui-filled trip home, TCM-channel surfing, or a foray into dating a cinephile, I’m guessing you’ve seen Casablanca, Notorious, Bells of St. Mary, Joan of Arc, or the rather unfortunate adaptation of For Whom the Bell Tolls, all of which star Ingrid Bergman.

What you probably don’t know, unless your grandparents were really into telling you which stars were actually trollops (Dear Lana Turner, my granddad thought you showed too much skin!), is that the woman who starred in these films, Ingrid Bergman, endured a scandal that was larger, and had more profound effects, than Tiger Woods’ and Tom Cruise’s scandals combined.

The story is pretty straightforward: Ingrid Bergman was born in Sweden, married a much older doctor, had a child, and attracted notice for her Swedish films. David O. Selznick (the producer behind Gone with the Wind) went over to Sweden and shipped her straight to Hollywood.

When Bergman arrived in Hollywood, she refused to undergo the makeover that most Hollywood stars endured. She didn’t want a new name, didn’t want to wear thick pancake make-up, didn’t want to straighten her hair, and rejected all attempts to pluck her bushy Nordic eyebrows. But Selznick was a smart guy (he was, after all, the guy who managed to convince America that a Brit could play Scarlett O’Hara) and decided that Bergman’s image would be NO IMAGE AT ALL; the anti-image, the un-Cola of stars. Bergman was thus sold as the “Nordic Natural,” a beauty immune to Hollywood’s machinations.

Bergman then appeared in a series of films that helped buttress her image as pure, virginal, and the type of woman who would never make googly eyes at your boyfriend. Sure, her character cheated on her husband with Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca, but,

a) She totally thought her freedom-fighting husband was dead

and (spoiler)

b) She gives Bogie up so the Allies can win the war.

Plus she played a NUN (I’m not talking a Sister Act nun, but a real, wimple-wearing, celibate nun) and Joan of Torched-on-the Stake-for-God’s-Glory-Arc. Which is all to say that Bergman seemed to mean one thing: an unsullied testament to the natural goodness of women the world over. The simplicity of Bergman’s image was a huge part of her popularity, just as Jennifer Aniston’s always-a-bridesmaid-never-again-Brad-Pitt’s-bride is a huge part of hers (right?). But it was also the source of Bergman’s “downfall,” as will become clear.

In the late ’40s, Bergman wrote an adorable letter to Italian Neo-Realist director Roberto Rossellini — a man known for womanizing, owning the shit out of the beret, and wearing sunglasses when most people in America were still squinting into the sun. But look at this letter — it’s clear this woman was a spectacular flirt:

Dear Roberto,

I saw your films Open City and Paisan, and enjoyed them very much. If you need a Swedish actress who speaks English very well, who has not forgotten her German, who is not very understandable in French, and who in Italian knows only “ti amo,” I am ready to come and make a film with you.

Ingrid Bergman

Dear Roberto! I AM READY! I will leave my husband and come to Italy to make a sexy black-and-white cultural commentary film with you!

Bergman was obviously hard to refuse (can you imagine Rossellini receiving this note? I picture immediate telegraphs to his Neo-Realism dude-bros: “Dear De Sica and Visconti, I got the Nordic Virgin!”). For the lead actress in his next film, Stromboli, Rossellini replaced his previous lover (Anna Magnani) with Bergman, and legend has it that Rossellini bet a friend he could bed her in two weeks, which may or may not be true but definitely makes the story better.

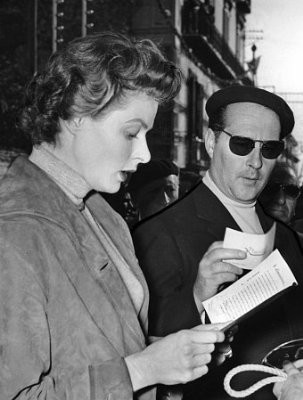

Rossellini apparently won that bet, because even before filming, the two were flirting in the way that people do when they know against-the-rules sex is in their immediate future. There’s a photo taken in Hollywood before they left for filming (when Rosellini came to visit, he stayed at Bergman’s house) that just drips with tension and anticipation.

But once the affair started in earnest on-set in Italy — complete with photos of them holding hands — the shit hit the gossip mongering fan. Bergman denied rumors of pregnancy to gossip columnist/moralizing-old-biddy Hedda Hopper, even though she was at least three months along, and so when Hopper’s arch-rival Louella Parsons announced the pregnancy days later, Hopper retaliated by mean-girling and slut-shaming Bergman as thoroughly and frequently as possible. Ed Sullivan refused to allow Bergman on his show, and she was denounced on the floor of the United States senate as an “instrument of evil.” (Can you imagine? That’s like Michelle Bachmann decrying ScarJo for shacking up with Sean Penn, which, OK, yes, I can totally see happening.)

Bergman’s husband refused to grant her a quick divorce, effectively ensuring that Bergman would give birth to a “bastard child.” Of course, Bergman’s virginal image didn’t mix well with “bastard child” and “Italian love affair.” And when an image and an action clash, scandal occurs. But the Bergman scandal was less, say, Evan-Rachel-Wood-dates-Marilyn-Manson, and more Tiger Woods-has-sex-with-dozens-of-prostitutes-and-leaves-the-tampon-in-the-parking-lot (remember that?). Because Bergman (like Woods) had refused to participate in image manipulation, her image seemed to mean one unified thing, rather than many complex things. In other words, her image wasn’t nuanced or detailed enough to explain why she’d run off with an Italian director and given birth to his child. There were attempts to do so after the fact — the husband was too old; she’d never really had a romance — but the damage was done.

But here’s the thing. This was the early ’50s, and morals — and understandings of how a woman should behave — were changing. It wasn’t like sexing up Italians was commonplace, but as the Kinsey Reports, Marilyn Monroe, and the debut of Playboy would suggest, sex was increasingly visible, even speakable. But the revelation of Bergman’s own sexuality was, in 1950, just too fucking much. With that said, the scandal did effectively make sex speakable, if still “evil.” Discussions of whether or not she should be forgiven, whether between friends, within the fan magazines, or on the senate floor, were essentially discussions about what sort of behavior was and was not acceptable when it came to women.

Bergman fled America, made some more neo-Realist films with Rossellini, gave birth to the “bastard” and a pair of twins (including Isabella Rossellini), and didn’t return to Hollywood until the late ’50s. Bergman’s scandal is thus a lesson to all flirts: beware Italian dudes, be even more wary of old biddy gossip columists, always (never?) let your employer pluck your eyebrows, make sure you tell contradictory stories about yourself to everyone you know so that when you do something outrageous it’ll be somehow explainable, and if you’re going to exercise sexual agency, make sure you don’t do it in the early 1950s.

Anne Helen Petersen is a Doctor of Celebrity Gossip. No, really. You can find evidence (and other writings) here.