Hiding My Secret (White) Boyfriend From My (Bangladeshi) Parents

by Nadia Chaudhury

I lead two lives.

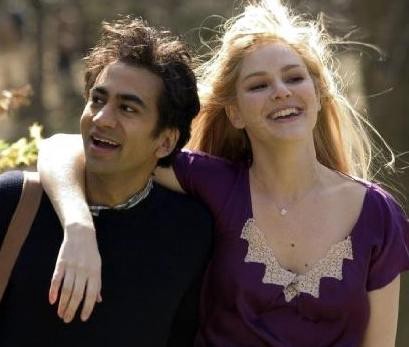

In the first, I’m in love with my boyfriend, Josh, of three and a half years and going strong. We go on road trips to Memphis and Montreal, we explore abandoned hospitals, we’re a writer/photographer duo — he reviews and I shoot concerts, he showers me with rabbit paraphernalia, I send him lyrics that remind me of us.

In the other life, the one I present to my parents, Josh-the-boyfriend doesn’t exist. I go to work, I hang out with friends, I go to concerts, I take pictures and write occasionally, and that’s about it. My parents don’t know about us, and it bothers me, but it’s what I have to do in order to be mostly happy with my life.

My parents have different expectations of what my life should be like. Dating doesn’t exist to them. Eventually, they expect me to marry a Bangladeshi Muslim guy of their (and to an extent, my) choosing. I don’t have the heart to tell them that that’s never going to happen. And so, because it’s easier, and because I’m terrified of what the outcome would be, I’ve kept my relationship a secret.

American (read: white) boys disgust my mother. Constantly I’d hear about how they’d use me for a day before throwing me out like garbage. (She uses much more colorful language that’s untranslatable.)

Before Josh, there was David, my first boyfriend, a high school love that we tried to extend into college. We failed. When we broke up, part of me was glad I never told my parents about him (though he was Chinese, not white). I didn’t have to prove her right.

My parents grew up in another country with a different culture. I’m their first-born, the first generation American in the entire family, the first to get my bachelor’s and Master’s degrees. I’m the oldest kid in my family, too, and my Bengali nickname, Sharna (“gold”), reflects how much I mean to my parents. I was the first in my family to experience the American way. I did things my parents weren’t familiar with: I listened to songs that were not-so-subtly about sex (I’m looking at you, Tori Amos), I watched TV where unmarried people kissed and went all the way (gasp!), and I stayed out late with friends at parties where I smoked and drank. My rebellious youth made things easier for my younger brother and sister — my parents don’t even bother calling to check up on them when they’re out late. I paved the way.

My parents had an arranged marriage — my father’s parents set up meetings with suitable women in their village in Bangladesh, and that’s how he met my mother, the only woman who dared to show up with a broken sandal. He liked that about her; he thought she was brave. So he picked her. She was an elementary school teacher with a Master’s in political science, and he was an engineer. Their marriage ceremony was elaborate, which Bangladeshi tradition called for. In the photographs, I see my mother wearing a red sari adorned with heavy gold jewelry everywhere. I see my father in a traditional suit. They don’t look happy — they look solemn. This is just a step for them. Afterward, he whisked her away to Saudi Arabia, where he worked for the royal government until they decided to give up their jobs and education to move to New York for the sake of their future children, for me.

My parents assume I’ll go through the same steps: Relatively soon, because I just turned 26, my mother wants me to tell her that I want to get married. She’ll arrange meetings with grooms-to-be. I’d pick the first decent guy to be my future husband. We’d get married, have babies, and live happily ever after. They did it, their parents did it, their grandparents did it, and even my cousins did it, so I’m supposed to do it as well.

It’s not to say my parents aren’t happy — they are, in a way, but they still had their bumps. They fought a lot when we were younger, and I vowed I’d never be like that. I wanted to end up with someone I completely love, someone I knew through and through, not from a parent-approved blind date. I don’t want to plan the rest of my life so far in advance. I’ve got time to do that.

Josh is the furthest thing from who my parents expect me to spend the rest of my life with — not only is he white, he’s Jewish. Being with him involves a lot of lies, or at least omissions. I’m vague about the things I do (“out with friends,” rather than “making out with Josh”), but my parents don’t push any further. The less they know about my life, the less they have to worry about the things I actually do.

(Once, during the first year of our relationship, I snuck him into my childhood apartment, where I still lived because I just graduated. I timed it right: My parents were at work, my siblings were at school. It was thrilling in one sense, I was like every other teenage girl, even though I was 22 at the time — I had a boy! At my house! But at the same time it felt wrong, like I was sullying my childhood home. I also worried that my mother might come home unexpectedly and we’d have to work out an escape route, which would’ve been tricky in an apartment with one entrance. We only did that once.)

He knows that my parents don’t know about us. He says he’s fine with it. Still, I worry that it gets to him. Wouldn’t he want a normal girlfriend, the kind of girlfriend who could bring him home and have family dinners with him? Even as I write this, I asked him why he was OK with this secret. “Because I didn’t fall in love with you knowing that,” he said. “It’s be weird if my feelings for you depended on what I thought of your parents.”

Not to say that he doesn’t know my parents or vice versa. They’ve met before, under the guise of him being my friend (much to their displeasure at the fact that I have male friends). They know him as the guy who accompanied my sister and me to the Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows book party at Barnes & Noble (we weren’t dating at that point). My sister knows about Josh — I told her in a few months after we started dating. I was terrified, but she already knew, she could tell we were together. It makes me feel awkward sometimes, like she’s an unwilling accomplice to the crime I’m committing against my parents’ honor. When we get into arguments, she’ll throw it in my face. “How could you do that to them?” she’ll yell. The burden is supposed to be mine to bear, not hers.

Last spring, my family moved from my childhood apartment to a new house in Queens, and Josh came to the housewarming party. I invited a bunch of high school and college friends as well, but I still was nervous. I made him walk the 30 blocks from the subway stop to the house rather than taking the bus just so he wouldn’t be the first to show up. He was still early, but he helped my father and brother set up chairs and tables. Could they tell he was more than a friend? Soon enough, he was one of the few white guys there among my friends, and my parent’s friends and relatives.

My father invited an imam, a religious leader from the nearby mosque, to the party, and the men gathered in the living room to commence blessing the house. Josh wasn’t sure if he could be in the room. I wasn’t either, especially because he was wearing shorts (can guys show too much skin in Islam?). He stayed out on the porch, looking at his phone while the men prayed and the women, myself included, stayed out of the way upstairs. He was one of the few who stayed until the very end, though, helping my father fold the chairs and throw out the garbage. Good impressions, right?

His family knows about me. I’ve met them all several times: mother, father, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, half-brothers. I spent a recent weekend upstate at his childhood home with just Josh, his grandparents, and his mother (and our two guinea pigs). His mother once emailed me, curious about my situation. I explained briefly. She wrote back that she understood, and she was in a sort of similar position with his father (who wasn’t Jewish, and now they’re divorced).

Attempting to deal with my secret feels embarrassing. Thanksgivings, for instance, are the worst. I’d want nothing more than to be able to bring him to try my mother’s Bangladeshi-style dishes and our spiced turkey. But, instead, I have family dinner in Queens, he has dinner at his uncle’s in Westchester, and we have our own post-Thanksgiving tradition where we eat leftovers from our respective meals the day after.

Due to circumstances, Josh had to move back home for a short period of time. When he’d come down to the city for concerts and events, we would have to work out elaborate plans of staying at friends’ places for the night. I even shelled out for a hotel room once. The concierge teased me, after looking at my information: “Do you want a New York City map?” I told myself at least it wasn’t an hourly motel.

In a perfect world, we’d have our own apartment together and we wouldn’t have to worry about my parents. In an even more perfect world, he’d be welcomed by my parents into our house for the night. Although it doesn’t look like either one of those possibilities will be a reality soon.

One friend always asks, “Do they not know still?” Another always asks, “When will you tell them?” My friends grew up dating in front of their parents, so what I do is strange to them. I have another friend who is in the same situation as I am, and she hasn’t figured out what to do either. When I stop to think about it, I get it, it is weird, it’s not ideal. Once Josh and I are stable enough in our lives (permanent jobs, savings, all of that real life junk), I’ll be ready to tell them, or so I’d like to think.

I know my parents have to know, to some extent. It’s just a matter of whether I want to confirm their suspicions, but I just can’t. It’s tough trying to reconcile my parents’ upbringing and expectations with what I want. My happiness should matter, right? That’s what I keep telling myself.

If I did tell them, I have no idea how my they’d react, and I’d like to prepare for the worst. Even now, my mom talks about marriage every single time I see her. She alludes to the fact that “my time is ending,” and that I need to begin my life. Because having a career and a job isn’t as important as starting a family right now. My father, though, might be more understanding. He’s the one who supports my decisions in life and gave me the freedom to do what I wanted. He lets me make my own mistakes, and I like to think that he was the same way when he was my age, so he’d understand.

Sometimes, at dinner, I look at my parents and play out how they’d respond once the words come out of my mouth. I know he will be sad. I know she will scream. She’ll be a wreck. I hope he’ll ask if I’m happy and say that’s all that matters. I know it will break my heart. I wish I could be the kind of daughter they wanted me to be, I wish I could give them what they want, but I know I can’t. I can’t have the best of both worlds.

Nadia’s parents will most likely not find this, because they haven’t found this yet.